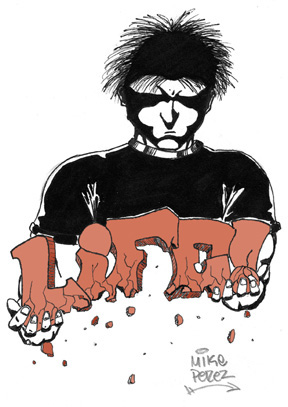

My struggle with depression

Joe, 18, became so depressed, he spent a few days in a psych ward to make sure he wouldn’t hurt himself. Reprinted from 1997.

Reprinted from September-October 1997

I was pretty depressed in junior high. In seventh grade three other boys made my life a misery. At nutrition and lunch, they chased me around the school. When they caught me, they’d push me around and say anything to demean me (which didn’t take a whole lot). It wasn’t limited to school. They also got my home phone number and started crank-calling me.

A few times I tried to fight back at school, but since I had never hit anything in my life, it was pointless the second I put up my fists. One day I picked up a board to defend myself. A teacher saw me and called me over. I thought maybe she’d help me. Crying, I told her all the pain they had made me feel. But when she talked to them, they twisted everything around and made me seem like a bad guy. They were let off and nothing changed. It made me feel like I couldn’t count on anyone to help me.

After that, I used to sit in my room and plan what to put in my will. I’d blame my death on the three bullies. I imagined my own funeral, wondering who would show up. I didn’t think anyone would come.

Things got worse in high school. I was one of the shadow kids. Skinnier than a toothpick, I wore braces and big plastic glasses like goggles. My hair was parted down the middle, forming two big puffs. I was afraid of other kids and sat like a rock at my desk, hoping no one would make fun of me. I broke out in a cold sweat when teachers called on me for an answer, or even when they asked me to get up from my seat.

Then my older sister moved back home with her wonderful two-year-old daughter, Ashley. My sister was always yelling at her child and treating her poorly. It drove me crazy to see it happening, so I fought with my sister all the time, sometimes right in front of Ashley. One day we had a major fight and Ashley started crying, afraid that I would hurt her mother. I broke down and cried, too. I went out to the backyard with my mom and told her that I couldn’t take the emotional abuse of living with my sister. I told her something had to be done. She did nothing. What could she do, really, kick her daughter and grandchild out on the street? I understood her point, but it made me feel even more alone. (I had to deal with it for a whole year until my sister left.)

As time went by, my depression deepened. I felt like the world was slowly fading away. My body was slow and heavy as if I was walking on the bottom of a pool. Just lifting up my hand to write my name was a chore that required much concentration. When I spoke, I felt like my words had to break down walls, and even then I couldn’t properly relate to anyone. Everything lost meaning. It’s like I was watching the world on the silver screen while I sat in the back row.I thought about giving some of my possessions away. What good would they do for me if I was going to die? Someone else should enjoy them. It was this thought that made me realize how deep my troubles were. I needed to talk to someone, and I reached out to my former teacher. He agreed to meet me at school. There in an empty room, I told him all my feelings and thoughts. He really listened. I continued to meet with him for the next few days, and he told me that he was worried that I might hurt myself. I agreed to meet him the next day at a counseling center to see if I should spend some time in a hospital.

That very night after I turned off the light and started to walk to my bed, I said to myself, "What in this room could I use to kill myself?" Then I caught myself. I knew it wouldn’t be long before I really did it.

The next day, as I waited for my brother to take me to the counseling center, my gaze went to the top story of a very tall building. I saw myself jumping through the window in an explosion of glass. My brother came and took me to the center. As I walked across the street, I stopped. I stood there, waiting for a car to hit me, but no cars came. My brother stared at me, seeing my dead eyes, and eventually I simply walked to the counseling center.

As I sat in the waiting room, I suddenly realized that if a car had come racing down the street, I would be dead. My breathing got heavy and quick, and tears welled up in my eyes. It scared me to realize how suicidal I really was. My teacher came in and introduced me to one of the counselors. After she heard my story, we decided I should stay in a hospital for three days because I was a danger to myself.

They called my mom and she drove me to the hospital. They put me in a private room as I waited for someone to take me where I was supposed to go. For the half-hour I waited, I was a wreck. I walked up and down the halls nervously, wishing I could run away. Then a man came and took me and my mom down a maze of hallways. The walls were closing behind me—even with a map, I couldn’t get out.

The psych ward was scary

Just before we reached the place for teens, I had to walk through the adult mental ward, where I saw people with towels on their heads, and others sitting in a corner all balled up. From there I came to what would be my home for three days. It was a hallway with rooms on either side. In one room there was a TV, a dining table and a refrigerator. Past that was a patio with 12-foot walls and no roof. I was more scared than ever, knowing that I would be with kids like the ones I feared in high school.

Suddenly three or four kids ran at me, bouncing up and down, asking, "What are you here for?" and "What did you do?" It felt really threatening. I quickly stepped into my room, which had only a table and a bed. I sat on the bed, feeling like I had just landed in prison. Soon after that, an attendant took my shoelaces and belt.

In the morning, I opened the shades of my only window. I had a front-row view of the adult mental patients’ patio. I saw people rocking in chairs as if they were zombies and pacing the grass in bathrobes as their arms flailed around. I closed the shades and felt a stab of fear. Would I end up like them?

As the day went by, sometimes we had planned activities (board games or cards) and sometimes there was nothing to do but sit there. We had group sessions during which about seven teens talked about why we were there. When it came to me, my mind went hazy and the words that came didn’t feel right. It was difficult to talk, especially in front of other teens who had more dramatic experiences like drug overdoses, drinking alcohol and swallowing pills. I felt like I was not accepted because what I did was not as serious.

Soon it got easier. As I listened to them, I realized these "threatening" teens were really troubled kids who also wanted help. They had courage for surviving this far. I began to feel connected to them. The more meetings we had, the more I wanted to talk. When it was time for me to leave, I wanted to take them with me and show them the best life has to offer. I was sad to leave, knowing that they would stay. I wished them the best of luck in whatever they do.

When I was let out, I remember walking out the front doors and stepping into the emerald city. Everything was beautiful, from the sun shining off the buildings to the sleek black of the street. It was all new and clean to me, almost like I saw it for the first time, and I was happy to be alive.

My counselor helped me

But my problems were not over. Later that day, my depression came creeping back and again I was contemplating taking my life. I saw a counselor who put me on anti-depressant pills. The pills didn’t make me walk around with a stupid grin all day, they just made my depression seem less overwhelming.

I continued to go to counseling, which helped me put the pieces back together and figure out what went wrong. I found out I was keeping a lot inside, even things from elementary school, like the time my best friend moved away, and another time when I accidentally broke another kid’s arm. I was able to link things together in a chain I could never see before. And I began to be free from that chain the day I decided to talk to someone.

I am thankful I didn’t kill myself because now I know that I would have missed something beautiful. No one is meant to die so young.

TeenLine (800) TLC-TEEN to speak with a trained teen peer counselor from 6 to 10 p.m.

Suicide prevention hotline (877) 727-4747

To be connected to the nearest suicide hotline (800) SUICIDE

Joe Taraszka graduated from high school and is working in construction. He is delighted with his son Christopher, who was born in 2002.

Joe Taraszka graduated from high school and is working in construction. He is delighted with his son Christopher, who was born in 2002.