Family comes first

With a strict dad, Yasamin, 17, doesn’t get to hang out with her friends that much, but she loves her Persian culture.

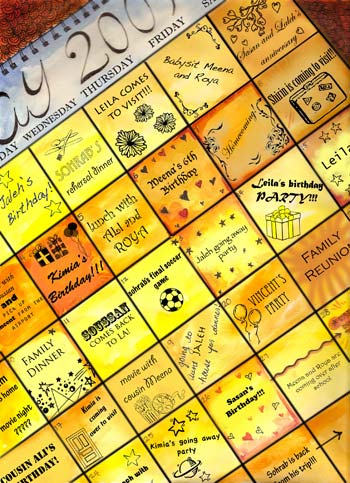

In July I was invited to my friend’s debut. It was a big event celebrating her 18th birthday with a court of her closest friends and beautiful decorations. I was so excited when she invited me, but I had to check my mom’s big calendar to see if I had family obligations.

My mom’s calendar is like God. It sits in the middle of our kitchen next to the phone, which is the center of my mom’s life. If I’m invited somewhere I have to go to the calendar and sift through the squiggles written in Farsi, and look through the appointment cards and invites taped all over to make sure I truly am free. I can’t read Farsi, so I have to wait until my mom comes home to read the illegible markings.

The calendar said we were free but my cousins from Paris would be here. My mom reminded me that I was a host to my cousins. Oddly enough, after I realized that I wouldn’t be going to my friend’s debut, I didn’t feel that bad. I love my cousins and was really excited to spend time with them. I didn’t argue or sulk. I knew that my family is more important.

I’m Iranian but I was born in America. Iranian and American cultures feel like complete opposites. Iranian culture is stricter than the way my friends live. It’s been a tug-o-war but I love my family and my culture and my life.

When I was a kid, I thought being Iranian was the coolest thing ever because I was different from the other kids at school. I learned to speak Farsi before I learned English. The big Iranian holiday Norooz celebrates the Iranian New Year, which begins on the first day of spring. My mom would come to my class before the New Year. She would explain the table setting by going through each item on the table and explaining the symbolism. My classmates would say, “That’s so cool! It’s better than Christmas! I wish I was Persian.”

My dad banned sleepovers

Pretty soon, though, I began to realize how strict Iranian culture is. In third grade, I went over to my best friend Simone’s house for a slumber party. My dad didn’t have a problem with it because he knew Simone and was close friends with her parents. We ate pizza, stayed up late, watched movies and painted our nails. It was fun. When I got home he said that I wouldn’t be allowed to sleep over anymore and that he shouldn’t have let me go that one time. I was shocked. I hadn’t done anything wrong and I didn’t understand what would make my dad change his mind. After I locked myself in my room, my mom came to explain why my dad had done a 180. My dad’s childhood Catholic school teacher, Father Larcher, had been staying with us. She said that Father Larcher told my dad that it was zesht, or inappropriate, that I was staying at someone else’s house. He reminded my dad that kids didn’t have sleepovers in Iran and that it wasn’t right for a child to not be in his or her parents’ home at night. I was so angry that I didn’t speak to my dad for a week.

As I got older, my dad’s strictness extended to other things. In middle school, it was all the rage to go to the Sherman Oaks Galleria and watch a movie. When people would invite me I was excited but I was never allowed to go. My parents didn’t want me hanging out in a mall at 10 at night after seeing a movie, because they didn’t want me to be “loose on the streets” as my dad described it. My parents also were selective about the friends I could hang out with. I wasn’t allowed to go to birthday parties, beach trips or amusement parks if they didn’t approve of the friends I was going with. I always put up a fight and would say, “You don’t even know my friends. If you knew them you’d like them!” But it always went in one ear and out the other with my parents.

But I began to see my parents’ perspective in the winter of eighth grade, when I visited Iran for the first time since I was a child. My mom took me to her old middle school and house. She told me about her experiences in Catholic school (my family is Muslim but my parents went to Catholic schools because it was the best education in Iran) and what she did with her friends. The most exciting thing they would do was get ice cream. My mom helped me understand that the sleepover thing is not just my dad, but it’s everyone in Iran. I realized that I didn’t have it that bad because I could actually go out with my friends and my parents let them come over.

I learned about my family’s history and what they went through during the revolution, when the monarchy was overthrown and replaced by a strict Islamic republic. The revolutionary government took her family’s house. It made me more appreciative and proud of my family. I respected my parents for keeping their values when they came to the United States.

My grandma, or Mommyjan, told me how hard it was for my dad to go to college and work in America, and how hard it was to adapt to the new culture and language. I began to appreciate why he’s so protective of us. He came here with nothing. He’s trying to keep us safe.

I still complained when he told me I couldn’t do something, but the Iran trip made me fight back a little less. My dad isn’t trying to be mean. He’s overprotective because he believes it’s right.

In high school my friends were becoming more independent but I was still stuck in my dad’s bubble. My dad is a typical Persian dad—strict, protective, stubborn and old school. He still acts as though we lived in Iran 30 years ago.

Junior year, when I got my license, I thought the freedom would be amazing. But my curfew was 11 p.m. and I couldn’t drive on the freeway. I couldn’t do the fun, late-night things my friends did. Pretty much, if it starts after 9 p.m. I might as well stay home, which is why I stay home—a lot.

Fortunately, my dad lets me go to high school dances when I ask but never without the usual questions: “Why do you want to go to the dance? Do you have a date? We didn’t have dances when we were younger.” He relaxes his rules for school dances because I’m in the safety of the school and its chaperones. When the Junior-Senior Prom came around I wasn’t allowed to go to the after party. Instead, I came home at midnight, put on sweatpants under my prom dress, and sat on the couch and watched TV. I didn’t think about sneaking out. I respect my parents enough to not disobey them.

I feel like I’m missing out on typical high school memories

I understand where my parents are coming from but I want to be a normal teenager too. High school is supposed to be about experiences and trying new things and I haven’t been able to do that. I don’t want to be that 30-year-old who never stayed out late and had fun with her friends. I understand that the independence I ask for is not a part of our culture, but we don’t live in Iran. I wish my dad would trust me when I deserve it. But then I understand that my parents are strict because their parents were strict so it’s all they know. They’re not trying to ruin my social life; they’re looking to the future and the adult I’ll become.

A lot of people think that Iranian women are oppressed and subordinate to men and to some extent they are. However, at its core, Islam aims to respect and protect women. Traditional Iranians believe in keeping their women safe from bad influences. One of my dad’s methods is making sure that my family doesn’t lead separate lives. We have dinner together every night. Even if I don’t want to eat I still have to come and sit. At the table we discuss what we did that day. We are first and foremost a family and family always comes first.

Like in June, when my friend had a going-away party because she was going to Lebanon for the summer. But we were going out to dinner with my aunt, my dad’s sister, so I had to go to the party late and could stay for only an hour. When I finally showed up I interrupted a movie. Some of my friends were not happy having to pause the movie while everyone talked. It was uncomfortable. I felt out of the loop because I hadn’t been there the whole time. Because of moments like these there are a lot of inside jokes that I don’t get. On top of that it’s never nice when I see a photo album on Facebook of a day my friends spent together and I couldn’t go.

When I tell my friends I’m going to Hawthorne for the day to be with my aunt, they don’t understand why I don’t just skip it to hang out. “It’s not like you never see her. What’s one missed trip to Hawthorne?” I say, “I have to go because she’s my aunt and my cousins are expecting me.” More importantly I want to go. My cousins are 6 and 9 years old and I want to see them and I know they look forward to seeing me too.

With kebob and belly dancers my family knows how to party

Even though I don’t do things other teenagers do, I do special things Persians do. Two summers ago we celebrated my dad’s 50th birthday. It was a huge bash with catering and a DJ that didn’t end until 3 a.m. My mom even hired belly dancers for entertainment. It was really fun. Most of my cousins were here from out of town. I had my entire family come over early. We were all getting ready, doing each other’s makeup, straightening each other’s hair, dressing up. The food came in, kebob of course, and it smelled amazing. My mom was in her five-inch heels taking fruit outside. When the party started and it got dark, it was fun. The whole time we were dancing and eating. It was nice to see my dad having a good time. This was fun dad, having fun with his friends, dancing and joking around with the belly dancers. When everyone left, my closest family members and I all hung out in the backyard. I was in sweatpants and we’d all kicked off our shoes. We sat around the fire pit and talked about the night. We opened the gifts and gossiped about who wore what. I thought to myself, “What other family does this?” It’s not always bad that our lives are not separated. I had fun and it was better than our school dances. If I weren’t Iranian, I wouldn’t have been a part of that.

I love that I have a big family and we’re all involved in each other’s lives. I may whine and complain and sometimes I admit I’m a total brat about the rules I have to follow. It can be hard being Iranian but I wouldn’t want it any other way.