A different kind of school

Even though 16-year-old Genesis’s school doesn’t have regular classes, books or finals, she feels like she’s getting a good education.

The minute you walk up to my high school, a very small charter school called CALS Early College High School, you can tell it’s different. The school is in an office building downtown, which we share with other business people wearing suits and carrying briefcases. To get to school I take the elevator to the third floor, but I don’t go to class. I go to my "advisement." My junior class of about 60 students is divided into three advisement groups that are always together for activities such as studying for the SAT. It is so small that it feels like a second home to many of us. We can leave our things wherever we want because everybody knows everybody. I often have trouble explaining to people how my school has no homeroom, no clubs, no cafeteria, no lockers and only one sports team—basketball. And when you become a junior, you enter "Senior Academy," where you don’t have any classes or books or finals, and no detentions.

You might be thinking that our school is weird. How can someone learn without classes or books? It’s crazy. That’s what I first thought when my advisors and my principal explained "Senior Academy." Since my class is the first class that will graduate from my school, we had never heard of this approach and didn’t know how it was going to work. The idea was for us to experience the real world by studying what we wanted to and learning independently. Each student would explore his or her passions through research projects and then make a presentation called an "exhibition" on what they learned. We take some classes, like math, at community college. In addition, we spend two days a week at internships in the community to get a taste of the working world.

As my classmates and I learned more, we liked the sound of the internships and having more freedom. We thought that it was going to be really easy to get through the year. I chose the topic of Web site design for my independent research; I thought it would be really cool to make my own Web pages. My friends chose topics like reggaeton, babies’ deformities, 80s style and the history of computers.

My friend Maria got an internship with the radio stations La Raza 97.9 and Latino 96.3. I got an internship with a legal clinic where people get custody of children whose parents were either incarcerated or in a rehab home because of drug use. (Usually the internship was my favorite part of the week because every person had a different story to tell.)

The first few weeks were very fun. In the morning, we did what was called "advisory activities": writing journals, SAT prep, reading and responding to assigned articles. Every afternoon, when we were supposedly doing our independent research, I was talking with my friends, listening to music on my friend’s iPod or we’d go to the library and go on MySpace. But then there was a change. The advisors realized that we weren’t doing our work and separated us. We were told that if we didn’t do our work we weren’t going to have anything to present in our exhibitions. Just the word "exhibition" made everyone scared. We were expected to cover science, math and history in our exhibitions. How was I supposed to relate those subjects to Web design? I started to worry—would I make it through high school? Would I have enough credits to graduate? How could I get my work done when the distractions were so tempting?

A lot of students felt so overwhelmed that they began to question the system. They asked the advisors to bring back regular classes like the ones we had during sophomore year. They were easier; everyone had the same homework and students could copy off each other.

But the advisors said that they weren’t going to change anything. I started wondering if I should leave the school.

My friend and I decided to visit Lincoln High School in Lincoln Heights and compare it to our own to see if leaving was a good idea. I visited a physics class where I saw students copying other students’ homework, talking or daydreaming while the teacher lectured. Students weren’t allowed to go out for lunch and they didn’t get to use laptops like we do at CALS. The hallways were crowded and teachers barely knew the kids’ names. I asked a student who the principal was and she didn’t know. It’s pretty scary not knowing who is running your school. At CALS the principal has an open-door policy and we can go talk to her anytime. Once in a while she even takes us out for ice cream. My friend and I imagined ourselves sitting bored in a dusty Lincoln classroom. We decided that we would get lost on Lincoln’s campus and that we would be better off at CALS.When I got back to school my advisor asked me why I wanted to leave the school. The truth was that I was scared of not getting all the credits I needed to graduate, but my advisor explained to me that she could help me manage my time wisely. She said that I could do it and I started feeling safe again.

It was hard to get my work done

As I settled back into the routine, I noticed that some days I would get a lot of work done and others I wouldn’t do much. I realized that I had fallen behind. My friend Maria and I decided to ask the principal for help. We made an appointment and explained that we weren’t getting our work done and all we were doing was fooling around. She looked disappointed and sighed. She said that we are supposed to do our work and we said, "Yeah, miss, but we were having fun."

She said, "Well, I have a daily planner that I use that you girls can also use." She gave us a calendar and a worksheet where we could schedule what we were going to do hour by hour. She assigned due dates. When I saw the worksheet, I said "Whoa—every hour?" After we left her office, we thought to ourselves, "Wow, we actually have to work."

The daily planner turned out to be harder than it seemed. We struggled to estimate how long our work would take and we still had a tendency to get distracted. We tried different things such as telling each other to stop talking, sitting by ourselves with headphones on and the music turned up loud and even studying in the principal’s office.

At the first exhibition, I was super nervous, but I did OK. In 20 minutes, I explained how I had learned to make Web pages, as well as describing the rest of my schoolwork—the books I had read, journals I wrote, and my internship.

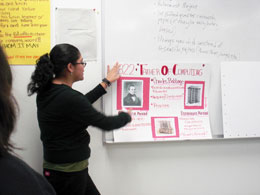

For my second project, I decided to stay with the same topic of Web design, and go more in depth into the Industrial Revolution, when new inventions started to change the world and eventually led to computers being developed. But I was getting bored with the topic of the Industrial Revolution, and it was hard to stay focused. I didn’t even read the books I was supposed to read. I just looked over my notes from a history class I’d had the previous year.

At my second exhibition, a few months later, I thought I knew what I was doing. I had a PowerPoint presentation on the Industrial Revolution and a poster on Web design. While I was setting up, the room started to fill with students, my advisor and even my vice-principal. I started wishing I had prepared better. I didn’t know how I was going to keep them entertained with my boring presentation. As I began, I stuttered and had to start all over again, but the more I talked, the less they wanted to hear. As I saw the bored students resting their heads on their hands, I started rushing through my exhibition to get it over with, and skipping over whole sections that I might have remembered if I’d had note cards. After I was finished, someone asked when the Industrial Revolution was. I had to admit that I didn’t know. I felt so dumb.

I walked back to my advisement and told everyone that my exhibition sucked. I felt like socking the wall. I was so mad at myself—I could have done so much better. My advisor agreed with me. "I told you," she said. "You should have done your work."

Facing the truth

My advisor stood up and called us together. She told everyone in the advisement that she was disappointed in the quality of our exhibitions. "You can’t go on like this. All you do is talk and waste your time." She covered her face with her hands. We all sat there guiltily looking at the ground.

She asked us, "What can I do so that you guys do your work? What do you need from me? Help me help you." Most of us didn’t know what to say because wasting time was easier than doing our work. We asked her if she could call home, send letters to our parents and have deadlines. But when we mentioned deadlines, she said, "I already had deadlines and you guys still didn’t do your work, so what are we going to do?" We stayed quiet. I felt bad because I knew she worked hard to help us and we still didn’t do the work.

I asked her to give me due dates for everything so that I actually do my work. Now every Friday everyone has something due from his or her projects so that more work is done, and our advisor checks to make sure. If you don’t, you lose your lunch privileges. For my third research project, I got five books from the library and took notes on what happened during the Great Depression.For my third exhibition, I chose a time slot late in the day when most of my classmates had left (I knew that if there were too many people, it would make me blank out like I did before). I practiced twice and I had note cards. As I explained how an economic crisis created the Great Depression, I was still nervous but I was able to control it. I described how some families were so desperate, they had to give their children away, because they couldn’t support them. Then I showed how the government tried to help people by creating jobs, even though some said the programs made the Great Depression worse. My advisor said she was impressed with my presentation and that I really knew what I was talking about. I felt proud that I did such a good job.

Overall I am really glad I go to CALS because it is a unique school. At times this school year, I was lazy and unfocused. But I learned from my mistakes. I’m more organized and break my tasks down into smaller pieces so that they are more manageable. In most classrooms you never really think about what you are doing. You just memorize a chapter, take a test and forget about it. Here you are required to think for yourself. In a public school they always say that students should be responsible for their actions, but they don’t expect it. They don’t let you make your own choices or be involved. I love that my school trusts me to decide for myself what I should study. It has made me feel that what I think and want really matter. I feel inspired to learn and am better prepared for the future.