Tookie Williams didn’t have to die

The execution of the Crips co-founder and convicted killer who later became a children’s book author made Eamon, 18, question our justice system.

When Stanley Tookie Williams, the Crips co-founder and convicted killer who later became an anti-gang advocate, was executed Dec. 13, I was pissed off.

As a teen you feel vulnerable and judged every day. Take just about any teen in Los Angeles and write down all the bad things he or she has ever done, and this kid might seem pretty horrible. At school if one teacher labels you a bad student, every teacher knows about it. But if you’ve done something bad, will you always be a bad person? With Tookie Williams it seemed that once he was convicted of murder, he would always be seen as a murderer. It’s judgement on the grandest scale—life and death.

I stayed up until 12:35 a.m. the night of Tookie’s execution waiting for the TV news anchors to announce Tookie’s death. I had hoped that people who shared my views would protest so strongly that the government would never execute someone again. But it was a quiet night, mostly made up of disappointed protesters talking to each other and holding candles.

Tookie had been hoping that Gov. Schwarzenegger would reduce his death sentence to life in prison for the four murders he was convicted of. The first murder victim was liquor store clerk Albert Owens, who Williams killed Feb. 28, 1979. Then he killed three members of the Yang family on March 11 of that same year. The governor was his last chance because the courts refused to overturn his conviction.

Up until his execution, Tookie denied that he killed these people. Tookie, who was black, claimed that the trial was unfair, because all the jurors were white. This is one of the reasons I was attracted to Tookie’s story. I was shocked to learn that as recently as 1981, 12 white people on a jury could decide whether a black man was guilty of murder.

Tookie’s execution came at a critical time in my life. About six months ago, I was arrested for drug possession, and sent to the Santa Monica jail for half a day. I had just turned 18, and they said I would be tried as an adult! I was terrified at the thought of jail and being around so many angry men, especially as skinny as I am. But I was also scared because I knew people’s opinions of me were about to drastically change. Would it be possible for me to be the Eamon they’d always known and a felon as well? During questioning I told one of the cops that I had screwed up, but added that he would not see me here again. He laughed and said "I hear that all the time, but you kids always seem to anyway."

I changed after being arrested—so could Tookie

After my mother bailed me out, I realized that I had lost my family’s trust. It seemed like they thought I became a very different person whenever I went out. My parents started asking who I had plans with. If I said names they didn’t recognize, then they didn’t want me hanging out with them. In the past my parents didn’t ask these questions, because they trusted me. I didn’t object, because I understood the pain I had caused them.

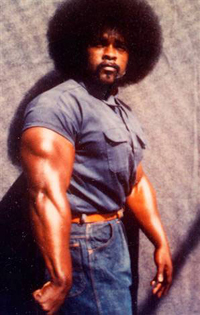

Media reports seemed to focus more on Tookie as a dangerous young man (above) than the gray-haired man he became (below left, posing with Minister Louis Farrakhan of the Nation of Islam, who supported him.)

Associated Press photo

As I learned more about the positive changes Tookie was making, I thought that killing him wouldn’t accomplish anything. In 1996, after 15 years of imprisonment, Tookie wrote his first anti-gang book, Gangs and the Abuse of Power, telling children about the dangers of joining gangs. By 2005, Tookie had published nine books. I remember seeing some of them in my middle school library.

Tookie’s lawyers asked the state Supreme Court to reverse his death sentence because he had changed. But the court denied the request. It seemed to me that society, especially the government, was turning its back on Tookie.

I had hoped that Schwarzenegger might see things differently. But in the end, the governor believed that because Tookie never took responsibility for the murders, he could not be redeemed, according to a story I read in the Los Angeles Times.

I think Tookie committed the murders. And I know it seems difficult to think of a man as redeemed when he’s not going to confess to a crime. But whether Tookie admitted to it or not, this is not what we need to talk about. If he’s in prison for life, a confession doesn’t matter. We should look at his actions, like writing the books.

I am not in favor of anyone joining a gang, but I understand why some people do. At least a dozen kids I know have taken that path, and it’s not out of the "thirst to kill and rob" as conservative Fox News commentator Bill O’Reilly said. In middle school I had a friend who came from a poor Latino family. He had no money, no father, and hung out with a lot of older dudes. Now telling him that joining a gang, which promised him money, respect and father figures is wrong, why would he believe you? I think he found power in a powerless area. And most importantly, living in a country that had turned its shoulder to him, he found a group that had his back. One of the reasons many people felt Tookie had not changed, was because he refused to help the cops by sharing his knowledge of gang tactics, according to the L.A. Times. But even though Tookie became anti-gang, we cannot forget that the Crips were once his family. They were still the people he grew up with and understood.

Executions send the wrong message

By the day of Tookie’s execution, his story was on every major news station. People like Jesse Jackson, Snoop Dogg and Jamie Foxx kept publicizing reasons to keep Tookie alive. They talked about his anti-gang children’s books and the Tookie Protocol for Peace, a peace initiative aimed at negotiating gang truces. The thing that was most convincing to me though was Tookie’s videotaped message for a truce between the Crips and the Bloods (more than 400 gang members watched this, according to www.democracynow.org).

By the day of Tookie’s execution, his story was on every major news station. People like Jesse Jackson, Snoop Dogg and Jamie Foxx kept publicizing reasons to keep Tookie alive. They talked about his anti-gang children’s books and the Tookie Protocol for Peace, a peace initiative aimed at negotiating gang truces. The thing that was most convincing to me though was Tookie’s videotaped message for a truce between the Crips and the Bloods (more than 400 gang members watched this, according to www.democracynow.org).

You may have seen Tookie Williams shown on the news as a young man—huge muscles from years of lifting prison weights, always walking in slow motion—rather than the gray-haired man he was in his final years. To me this was a subtle way to make him look less human. Despite his multiple Nobel Peace Prize nominations, despite the fact I watched on TV as members of the Bloods (the rival gang of the Crips) announced that if Tookie wasn’t killed they would disarm, the government still saw a thug. And his image outweighed everything else.

Many people felt Tookie deserved to die. They believed his execution would show current and future gang members that the country has no patience for gang crimes. But I feel differently. I think the government is saying that trying to change doesn’t matter. And even if you try to become a better person, the country will not recognize that change.