“I hate white people,” one of my Latino friends said to me during class freshman year. I was confused, but nodded in agreement because I always think my friends will get mad if I disagree with them.

“So do I,” I replied.

“Yeah,” my friend continued, “they’re so stupid.”

At this point he launched into a speech about his reasons for hating white people. “They’re so rich,” he said, “and ugly.”

Soon, I found myself nodding along with him. After all, I’m Chinese-American and therefore, one of those people The Man holds down. I thought I had every right to agree with him, and I even offered up my own reasons for hating white people.

“The teachers always favor the white kids,” I added because in my history class, the teacher always called on the lone white boy even when the rest of us raised our hands. “Those white people, I hate them so much because they’re snobby.” I remembered the stuck up white girls at my Catholic middle school squealing, “Oh my God! You’re gonna get shot!” when I told them I would be attending a public high school.

My examples seemed to satisfy my friend, and soon the bell rang. I was out the door and halfway down the stairs when someone tapped me on the shoulder. It was a friend of mine. She was white.

“Hey, Lia!” she said.

“Oh,” I said, looking at the floor, “hi.”

My friend noticed my discomfort. “What’s wrong with you?”

“Nothing,” I said quickly. As we walked to our next class together, I felt guilty. I called this girl my friend and yet I just spent five minutes putting down her race. I had believed everything I’d said about white people but felt that that most of those stereotypes didn’t apply to my friend specifically. I realized then that I’d been making generalizations, and I resolved to quit stereotyping my friends.

That same day at lunch, I was talking to that same friend when she asked me, “What’s the difference between Latinos and Filipinos anyway?”

I wasn’t sure what to say to her. “Well … Filipinos are Asian.”

“Oh,” she said, sounding unconvinced, “I get it.”

“Yeah,” I said and realized then that both my friend and I were ignorant about race.

I don’t think that only my friend and I have prejudices, though. In the back of each person’s mind, there are stereotypes and generalizations that influence his or her opinions about different races and nationalities. I’ve walked into classrooms, seen a group of Asians and thought, “Great! They can help me with my homework!” I know that a lot of my friends do this, too, because of the stereotype that Asians are good students.

Also, almost everyone I know has either told or laughed at a racist joke. This doesn’t necessarily make them bad people. It just means that they, like everyone else, have biases. I don’t think it’s something that can be cured completely, but we can all learn to recognize when we’re acting prejudiced and try to understand why.

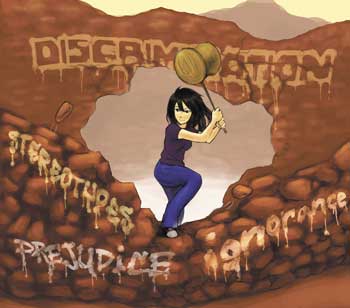

We need to discover why we make assumptions about each other, so that we can eliminate the source of our preconceived ideas. That way, when we meet each other, we won’t judge each other so quickly.

Having diverse friends doesn’t mean we’re tolerant

The most pathetic excuse I’ve heard people use to prove they’re not prejudiced is “But I’m not racist! I have [insert race of choice] friends!” Just because you have friends who are a different race does not mean that you understand them. It’s impossible to fully understand a race or culture if you’re not part of it. In fact, having friends of different races can just delude people into thinking they’re being tolerant, while still making secret generalizations and assumptions.

I can’t even count the number of times that my friends have made offensive remarks about Asians or Chinese people in front of me. When I was in seventh grade, my school was having a cultural festival, and all of the students were supposed to wear clothing from different cultures. One of my best friends at the time was a white girl and she wanted to wear a Chinese dress.

We decided to trade cultures: She would be Chinese and I would be European. We discussed how we would do our hair and what make-up to wear. Then my friend mentioned changing her eyes. I asked her what she meant.

“I’ll have to pull them back,” she said, pulling the corners of her eyes back with her fingers.

I felt like jumping up and down and screaming, “Hey over here! Have you ever looked at me before?” My eyes aren’t huge, but they’re double-lidded and not shaped like slits. Even my friends with single lids have slightly round eyes that look nothing like what my friend would have looked like with her eyes taped back. So why hadn’t my friend noticed that?

The cultural festival was supposed to be about sharing and understanding each other’s cultures. I wondered how much “sharing and understanding” my friend was doing by assuming that all Asians have slanted eyes. Instead she could have learned that in 1882 the United States passed a law that barred Chinese from entering the country, consequently creating a bachelor society because men couldn’t bring over their wives and children. She could have also learned that before China opened to America in 1972, the majority of Chinese-Americans were American-born, not immigrants, because people could not move between the two countries. But instead she chose to stereotype Chinese people. And if she was stereotyping, how could she be open to learning more?

I was too scared to say any of this, though, because I didn’t want to lose a friend. I didn’t know how to confront her. Saying “Hey, that eye-pulling thing is racist, so don’t do it again” wouldn’t explain why I was offended and would probably make my friend think I was insulting her. After all, who wouldn’t be insulted if they were accused of being racist?

I ended up saying, “I don’t have anything to wear that looks European. It’ll be easier if I just wear the Chinese dress,” because it was the easiest way to keep her from reducing my culture to rice-shaped eyes and those tight little dresses that choke you, while not having to confront her. I ended up wearing the Chinese dress. Later, I was embarrassed to realize that by wearing the outfit, I was reducing my culture to a stereotype as well.

Another time, in seventh grade, a classmate I had just met asked me what my first language was. When I told her English, she blinked at me and told me to be serious.

“I am being serious,” I said, annoyed because even though I had lived in the United States all my life, people still considered me a foreigner who grew up speaking a different language. “I’m third generation Chinese. My parents were born here, so they’ve always spoken English to me.”

“But you must have spoken another language before,” my friend said.

“Before when?”

“When you were little.”

“When I was little,” I tried again, “I spoke English.”

“You know that’s not what I mean.”

It didn’t seem like she would ever believe that my first language was English, so I gave up. “My first language was Chinese. I spoke it to my grandmother.”

My friend smiled and looked relieved that I had finally understood her question. “See, that’s what I meant.”

I learned an important lesson from that experience: It is impossible for an Asian person’s first language to be English.

I feel like people who believe things like that should be sent to their own little island where they can’t bother anyone. But then again, they’d probably have to send me too, because one of the reasons I was afraid to confront my friends about their frequent stereotyping was because it made me feel like a hypocrite.

I make judgments based on stereotypes all the time. Koreans, in particular, intimidate me because they’re intelligent and always perfectly dressed. I wish I were that smart and fashionable. In school, the people at the top of the class are always Korean. One of my Korean friends told me that Koreans are rude, shallow and materialistic, and that description has stuck with me. Whenever I see an Asian person who is perfectly groomed and is carrying around an expensive-looking cell phone, I always think, “That person must be Korean.”

Usually, I’m correct, but that’s probably because most of the Asians at my school are Korean. I’m sure if I lived in a community with a large number of Chinese I would see lots of Chinese people with expensive cell phones. Materialism applies to everyone, not just Koreans.

I once told my cousin about the people at my new middle school and how much I disliked the Korean girls because they spoke Korean all the time when no one else could understand them. My cousin stared at me for a few seconds and shook her head. “Aren’t a lot of your friends Korean?” she asked.

“Yeah,” I said. “So?”

Looking back, I’m embarrassed that I hadn’t understood what my cousin was really asking: “Why are you stereotyping your friends?”

My ninth grade English teacher once said, “Tolerance isn’t trying to understand someone you don’t like. It’s keeping yourself from punching him or her in the face.” Her definition of tolerance bothered me because it could make people think that they’re not prejudiced because they’re not committing hate crimes or using the n-word.

Learning about other cultures helps us connect

It’s because I was just “tolerating” my white and Korean friends that I was able to put them down behind their backs. My friend who had wanted to “dress up” as a Chinese girl was maybe doing a little more than tolerating my heritage, but she wanted to regurgitate a stereotype, not learn anything new about my culture. Neither one of us took the time to understand each other’s cultures because we believed the little understanding we had of them was enough to “tolerate” them. We should all try to learn what other people’s cultures mean to them. A classmate once showed me a picture of her favorite Korean singer. Normally, with people who don’t speak Korean, this classmate talks only about school. I was flattered that she felt comfortable enough with me to share part of her culture.

I think that’s why I don’t like it when people say, “I don’t care what race my friends are,” because it implies that they don’t care about their friends’ cultures, and since culture is such an important aspect of most people, I find it difficult to believe that these people know their friends that well. These people, myself included, are often too afraid of offending others or appearing prejudiced to actually get beyond, “I think racism is bad. People of different races should mix more, and it’ll get better,” when they discuss topics like school integration and therefore they are unaware of whatever stereotypes they have.

Well, the only way to deal with a problem is to acknowledge that it exists. I’ve become more aware of when I use stereotypes. Last semester, my friend was talking about going to a $5,000 summer program, and I remember thinking, “Of course you can afford that. You’re white.” Before, I wouldn’t have caught that I was thinking such an obviously prejudiced idea. I think that if I keep noticing myself doing that, I’ll eventually stop stereotyping.

Prejudice comes from ignorance, and I don’t know many people willing to admit their stupidity. But I’m good at being stupid, so I’ll go first: “Hi. My name’s Lia, and I’m prejudiced.”