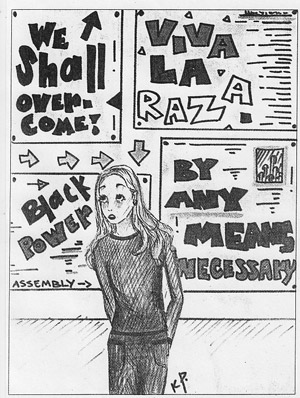

Another school assembly, another cultural pride presentation—for more of us students, it’s something to sit through and be bored at. We get out of classes for an hour or so, we clap at the speeches and dances, and after lunch, we’ve forgotten about the whole event. So how could such a negligible aspect of school life cause tension between students at a racially idyllic school? Why were these “celebrations of culture” making me feel awful about my own background as a white person?

At my school, Immaculate Heart, there are a few off-color jokes and insular cliques, but on the schoolyard there’s harmony. My group of friends have so many varied backgrounds: Black, White, Caucasian, Mexican, Irish-Japanese, Egyptian, Russian, Filipina-Chinese, European-Korean. Most of the time we don’t even think about coming from different cultures, but one of us once teased that we’re the “real” Multicultural club.

The school’s Multicultural Club seems to be one of the only things I’ve encountered that doesn’t seem to be multicultural. They’re in charge of running most of the cultural learning assemblies, which all students and teachers are required to attend, but an upperclassman told me that one ethnic group “takes over” the club every year. Members of this year’s Multicultural Club say it’s because people of only one group of people want to run the club—everyone else wants to participate only in the “fun stuff” like the performances.

When it was Día de la Raza, the Multicultural Club showed a skit about how the Europeans conned the native Central Americans. Three Latinas played the parts of European explorer, conqueror, and priest; they gave simple props, like a book representing the whites imposing their religion, to the girls playing the natives. They responded with scornful statements like, “The white men… slaughtered and raped our people.” “The whites…gave us their God, but enslaved us under the pretense of glorifying Him.” “The Pale faces… took away our land, and gave us blankets in payment. But the blankets had covered their sick soldiers, and we died by the thousands.

Ever since I was very young, these kinds of presentations and assemblies made me acutely aware of people’s resentment of whites in history. Until this point, I accepted it. But during this skit, my first thought was “Oh no, not again.” I finally realized how sick I was of presentations that focused on the atrocities of whites to almost every other cultural group. Instantly disgusted with myself for thinking that, I suppressed these thoughts by telling myself, “Oh no, how awful,” for I knew the full reality of what my ancestors had done was worse than what the people in the skit were showing us. These things are skimmed over in history class—treated as a statistic instead of something tragic and cruel. Perhaps that is one of the reasons why the skit was so vehement—so that we students would learn and remember. But I don’t even remember anything else about the assembly except my feelings about that skit—I barely knew what Día de la Raza was, anyway, although I wanted to learn.

In my opinion, the second Multicultural Club assembly, for Latino History Month, got off to a great start. There were interesting poems by Latino authors, like “Oranges” by Gary Soto, and one about a princess read in Spanish with an English translation. Costumes, dancing, two girls with beautiful strong voices sang songs by Selena and other artists. I felt relieved and started to enjoy the program; this was a celebration of culture and pride, not victimization.

A performance got out of control

We were informed we would be treated to a special guest presentation from a family of a tribe descended from the Aztecs. About eight men and women filed onto the stage. I drew in my breath at their amazing costumes: gold armor, silver helmets, and magnificent feather headdresses, beautiful and elegant in their own way. Two men started beating their great drums, and an intricate, spirited dance began. Soon, the leader of the dance came to center stage, an old man holding sticks and bowl, much older than I assumed when he was dancing as energetically as his 20-something relatives. Smoke filtered from his hands into the audience, and we were intrigued—surprised to see fire in the auditorium. Straining forward as he came to the edge of the stage, he began to tell us of the greatness of the Aztecs in a clear, deep voice, mingling his descriptive words with Spanish, gesturing with his flame. Slowly, he gained momentum as he began to talk of the coming of the Europeans. His voice became agitated, and his movements began to seem violent. Most importantly, his words began to rake up all the wrongs the whites had done, old guilty sores I had felt. “They enslaved us, raped us, broke our people, but we survived.” What was he planning to do with the fire? His speech became more venomous towards the whites with words like: “The white ones were a curse, selfish, cruel, burning out people, and it continues to this day, when our culture is still suppressed.” I told my friend how bad this was making me feel, and she whispered back about how torn she felt, being part Mexican and part white.

He dipped his hands in the fire, shouted more declarations along the same lines, some all in Spanish, and each time he did so, he punctuated his cries with passion and power, judging by the effect on the cheering audience. Finally, he covered his whole face in the flames as the drums beat into a crescendo. Suddenly, darkness filled the auditorium, and the only light was on him. The man started softly, but then continued with his haranguing of the audience. He started addressing the black people in the audience, how the whites enslaved their people, raped and beat them, how deep their suffering was, and finally, how ell they survived. Many African-American girls started cheering and making the “raise the roof” gesture. It seemed to me that yet another group was against us white people. But then I noticed they stopped cheering because he was tearing at his hair, screaming passionately in Spanish, even alienating the Spanish-speaking people.

It finally ended with a black-out; there were no closing words by any teachers. Shaken, we filed out of the auditorium. We spent our whole drama period discussing the assembly. Many white people were angry, declaring the tribe never should have come, explaining how the assembly was completely unfair. They said the man was lunatic, and a hypocrite for ranting in Spanish, the language of the Europeans whom he hated, instead of his own Aztec tongue. Some Latina girls agreed and felt bad, almost as if the white students were blaming them for it. Others defended the man, arguing that what he said was true and needed to be heard, and that he just got a little carried away. When other students scoffed, they told the class that finally, as if to make amends for everything, the man gave a blessing to all.

I agreed with the other white people because I thought he was going too far in making a whole lot of people feel bad. I pointed out that the blessing was in Spanish so it was little good to the Anglos whose ancestors he had railed against.

My friend Lily remembers that “It was an exciting and an intense assembly. What he was saying was true in some ways, but I think it was too much at one time. It was probably the excitement of the performance that made it too much. If it was said calmly over a presentation, then maybe it might had have a different effect. Then he had to go and dump his face in the fire, which freaked more people out, and caused more tension between students.”

Finally, an assembly I could enjoy

A few months after the Latino assembly, the Multicultural Club had their Black History Month assembly. Yet this seemed different from the start, even in the planning stages. For almost a month before, daily announcements and bulletins asked everyone with something to present or perform to join in. The result of this was that many Black girls—most of whom didn’t belong to the Multicultural Club—joined in and got their friends of different backgrounds to help out.

During the assembly, slavery was touched upon, but it was not the focus, rather the culture of black people in America, colorful and diverse. Poems by Maya Angelou were recited with feeling, there was music, speeches, and stories. The presentations were interesting and informing to non-black people like me: one telling the life stories of great black women from their point of view, and one about how the black and Native American peoples mingled. There was also a dance medley by African-American girls: lovely ballet, graceful modern, interesting tap, and rap. After a brief showoff African-influenced costumes, we were treated to dances from Africa, Jamaica, and the US—performed by people of all different backgrounds, which gave me pride that our school was so diverse and there truly seemed to be “no color lines.” My friend Lana said “I liked the Black History Month Assembly. It wasn’t a lecture, it was fun learning.”

Toward the end of the assembly, it was time for the Black National Anthem. Everyone stood up immediately in honor of it. And the person at the mike didn’t say, “If you’re black, sing along.” She said, “If you know it, sing along.” Well, I knew it! I had been taught it in sixth grade and kept it in my memory, because it truly is a beautiful song. And I didn’t see any reason not to sing along. I felt proud to be included.

l

Black National Anthem

Life every voice and sing, till earth and heaven ring,

Ring with the harmonies of liberty

Let our rejoining rise, high as the listening skies

Let it resound loud as the rolling sea.

Sing a song full of the faith that the dark past has taught us,

Sing a song full of the hope that the present has brought us,

Facing the rising sun of our new day begun, let us march on till victory is won.