Starting over in America

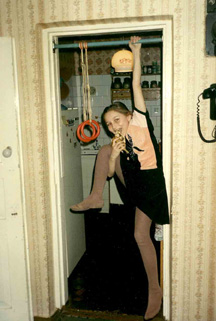

Eugenia, 16, never thought it would be so hard to adjust to life in America when she moved here from Tajikistan.

At long last, my teacher chose me to sing a solo in my school chorus, one of our only forms of entertainment in my hometown Dushanbe, Tajikistan—the republic was established in 1991 after the breakup of the U.S.S.R. I rushed home to tell my parents only to discover that a week before the concert, we were moving. I felt so mad until they said where we were moving—to America!

Man, was I excited! Imagine me, living in the land of opportunities, with lots of tall buildings, cool skater kids and super models all over the beach. Ever since I was little, I knew that one day I’d live in America, which is often put on a pedestal by the former Soviet Republics and other European countries. Every Saturday after school, my friends and I went to the park, rode the swings and fantasized about the American roller coasters that we saw on TV. Now I’d finally get the chance to ride them.

I felt so happy that I forgot about the chorus, my dear pets and friends who I’d leave behind. We’d say farewell to our huge house. It had been in my dad’s family for generations and was the biggest one on the street. Compared to others, we were well-off since most houses were only two or three rooms. Our house had three bedrooms, a pretty veranda and an awesome garden where we grew the most delicious fruits that I sold to our neighbors. We had the best raspberries and peaches around.

Nope, I was ready to go to America. After all, who wants to wake up every morning by 6 a.m. to stand in line and buy bread? You had to, if you wanted to eat. The bread was always brown and once in a while, you’d find a little stone in it, because it wasn’t cooked in clean conditions. In Tajikistan, food was rationed—one half-loaf of bread to one person each day was the rule.

Grocery stores like Ralph’s and Vons don’t exist there, only open markets called bazaars where you shop for meat, nuts, grains and everything else every Saturday. Milk always tasted diluted with water. Good milk and cream cheese came from Moscow and was expensive. We only ate bananas and oranges during Christmas time. Clothes were either homemade or passed down. There were no malls or amusement parks. Hell, it was the middle of the civil war!

We walked to most places or took the bus, which was always packed and had a horrible stench from sweat!

I couldn’t wait to get to America

My family decided that my mom and I would fly to America first. After my dad finished his business in Tajikistan, he’d join us.

I thought we’d hop on a plane from Moscow and land in Los Angeles, but no. We drove to Tashkent, the capital of Uzbekistan—a country bordering Tajikistan. From there, we flew to Amsterdam, got off the plane and flew to New York.

Everything was so strange

We got off the plane in New York and waited for our connecting flight to Los Angeles. My mom had to run an errand, so she left me sitting with the suitcases. That was fine with me, because I was exhausted. I sat there next to four fat people—a mom, dad and their two kids. They must have been waiting for a plane, but they talked so loudly. Plus, they were so overweight and their kids were hyper. It looked so strange to me, like something out of a cartoon. I felt so tired, frustrated and out of place that I started to cry and wanted to go home.

But when we finally boarded the plane and later landed in Los Angeles, I felt happy and thought the worst part was over.

My mom and I moved into a one-bedroom apartment with no backyard in Sherman Oaks, a big switch from my big house with a beautiful garden in Tajikistan. We didn’t own a car in Los Angeles and walked everywhere—to the doctor, to buy groceries, you name it. Although we walked in Tajikistan, the city of Dushanbe is way smaller than Los Angeles and we never walked as much as we did our first year in America. Before I could start school, I had to get shots. It was a long walk to the doctor’s office. By the time we reached it, blisters had formed on my feet. I walked back home with my shoes off.

There were other things about America that I had to get used to.

For starters, L.A. didn’t look the way I expected. I pictured big towering buildings, like the ones in New York. On TV and in postcards, all I ever saw was Beverly Hills, the ocean and beautiful stores. But Los Angeles mainly has short buildings and as a city, it’s really spread out.

In Los Angeles, millions of palm trees sway in the breeze. In Tajikistan, the only place you see palm trees are in a botanical garden.

People here smile a lot. Even strangers smile and say, "hi," which seemed weird. In Tajikistan, you only say hello to people you know.

But the main thing that stands out in America is that everybody drives! In Russia, if a woman drives a car, she seems masculine and strong. But here, even 16-year-old girls drive cars. These new customs felt weird, but I adjusted to them.

‘I don’t speak English’

I started middle school armed with the only English I knew: Good morning; My name is Janny; I don’t speak English; Where is the bathroom?; Thank you; Good-bye. When people asked me questions, I never understood and just replied, "Yes." If they looked strangely at my response, I’d say, "No, no, no." That was my way of answering questions.

Most of all, I didn’t know when someone made fun of me—and they did! I just took it all in and smiled. I felt like an idiot.

My inability to speak and understand English proved the most difficult part of living in America for my entire family. The school put me in their lowest classes with the thinking that if I couldn’t understand the language, how could I understand a math or science class? My self-worth was belittled by the school and the people around me.

When I left Tajikistan at the end of fifth grade, we studied algebra, botany and Greek civilization for history class. But when I came here, students were just learning how to divide, wrote stories about the Dodgers and for social studies we discussed the job of policemen. I was sure that I knew more than any of my classmates, but it made me feel as though I wasn’t good enough since I didn’t speak English. It really trapped me.

Since I thought American people were so smiley and happy, I never realized how hard school could be. Some of my peers said rude things to me—the immigrant. They said that immigrants caused all the problems in this country, but never realized that America was created and built up by immigrants!

But the most difficult part of all was the isolation. I had nobody to talk to and neither did my mom. Sometimes we didn’t support each other, because we were frustrated with our way of living and got on each others’ nerves.

I was determined to break out of the cycle. So every day after school, I’d write out words from books that I didn’t know, look up their definitions and memorize them. Even watching TV became an English lesson. Eventually I accelerated in school and by eighth grade I jumped into honors classes. It felt like I had crossed the finish line of a long race. Even then, I needed a tutor and spent two hours each night looking up words in the dictionary. But I was very proud to have learned English in two years!

Things progressed slower for my mom. In Tajikistan, she was an economist. But in America, she’s been anything but that. She worked as a housemaid and then an office clerk.

It was more difficult for my dad. He made me go places with him, since he didn’t understand English. He went from working as a big businessman in Russia to being unemployed here. He refused to take a lower paying job, but his language skills prevented him from getting anything else. So he stayed home and my mom went to work at a medical office. But he didn’t want to help out around the house because he considered that women’s work. These things weighed heavily on their marriage and eventually they divorced.

Slowly we have adjusted

A few years have passed since all of that and things are easier. My dad recently opened his own computer company. My mom owns a billing company.

As for me, I fluently speak English now and am working on perfecting my French. Next year, I plan to learn Japanese. I’m starting up my own newspaper called Tyro.

I’ve overcome my middle school experiences and have grown from them. I’ve learned not to fall to the same level as the people who made fun of me. There are lots of ignorant people out there and sometimes it’s best to ignore them.

Most importantly, I discovered that if you set your goals straight and focus on achieving them, despite what others say, things do come together. Looking up words in dictionaries, memorizing definitions, staying for tutoring and spending countless hours in the library paid off, even if I did seem like a nerd back then. I’m happy now and that’s what counts.